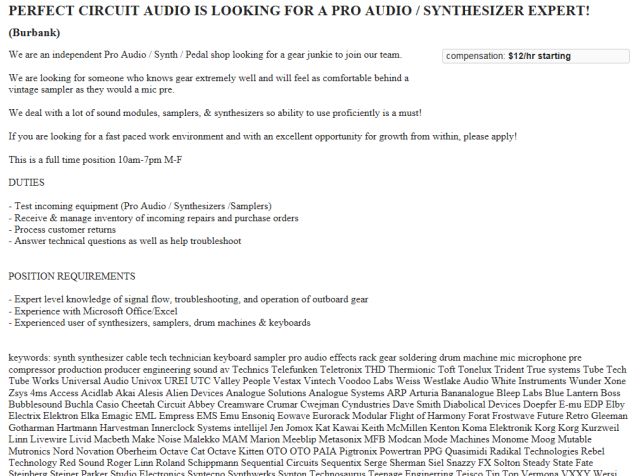

Have you seen this on popular nutrition sites recently? The data stems from research done by Johannes Bohannon, Ph.D. at the prestigious German Institute of Diet and Health.

Only problem is - this was an absolute hoax. For the inside scoop, read on - from io9:

I Fooled Millions Into Thinking Chocolate Helps Weight Loss. Here's How.

“Slim by Chocolate!” the headlines blared. A team of German researchers had found that people on a low-carb diet lost weight 10 percent faster if they ate a chocolate bar every day. It made the front page of Bild, Europe’s largest daily newspaper, just beneath their update about the Germanwings crash. From there, it ricocheted around the internet and beyond, making news in more than 20 countries and half a dozen languages. It was discussed on television news shows. It appeared in glossy print, most recently in the June issue of Shape magazine (“Why You Must Eat Chocolate Daily,” page 128). Not only does chocolate accelerate weight loss, the study found, but it leads to healthier cholesterol levels and overall increased well-being. The Bild story quotes the study’s lead author, Johannes Bohannon, Ph.D., research director of the Institute of Diet and Health: “The best part is you can buy chocolate everywhere.”

I am Johannes Bohannon, Ph.D. Well, actually my name is John, and I’m a journalist. I do have a Ph.D., but it’s in the molecular biology of bacteria, not humans. The Institute of Diet and Health? That’s nothing more than a website.

Other than those fibs, the study was 100 percent authentic. My colleagues and I recruited actual human subjects in Germany. We ran an actual clinical trial, with subjects randomly assigned to different diet regimes. And the statistically significant benefits of chocolate that we reported are based on the actual data. It was, in fact, a fairly typical study for the field of diet research. Which is to say: It was terrible science. The results are meaningless, and the health claims that the media blasted out to millions of people around the world are utterly unfounded.

Here’s how we did it.

Cherrypicking the numbers and p-hacking. Much more in the article - it is sad that much of scientific research suffers from the same corruption.

The same problem happens in some of the most respected Journals. Dr. Richard Horton, editor of the British medical journal Lancet has this to say (PDF):

Offline: What is medicine’s 5 sigma?

“A lot of what is published is incorrect.” I’m not allowed to say who made this remark because we were asked to observe Chatham House rules. We were also asked not to take photographs of slides. Those who worked for government agencies pleaded that their comments especially remain unquoted, since the forthcoming UK election meant they were living in “purdah”—a chilling state where severe restrictions on freedom of speech are placed on anyone on the government’s payroll. Why the paranoid concern for secrecy and non-attribution? Because this symposium—on the reproducibility and reliability of biomedical research, held at the Wellcome Trust in London last week—touched on one of the most sensitive issues in science today: the idea that something has gone fundamentally wrong with one of our greatest human creations.

The case against science is straightforward: much of the scientific literature, perhaps half, may simply be untrue. Afflicted by studies with small sample sizes, tiny effects, invalid exploratory analyses, and flagrant conflicts of interest, together with an obsession for pursuing fashionable trends of dubious importance, science has taken a turn towards darkness. As one participant put it, “poor methods get results”.

A bit more:

One of the most convincing proposals came from outside the biomedical community. Tony Weidberg is a Professor of Particle Physics at Oxford. Following

several high-profile errors, the particle physics community now invests great effort into intensive checking and rechecking of data prior to publication. By filtering results through independent working groups, physicists are encouraged to criticise. Good criticism is rewarded. The goal is a reliable result, and the incentives for scientists are aligned around this goal. Weidberg worried we set the bar for results in biomedicine far too low. In particle physics, significance is set at 5 sigma—a p value of 3 ×10–7 or 1 in 3.5 million (if the result is not true, this is the probability that the data would have been as extreme as they are).

The conclusion of the symposium was that something must be done. Indeed, all seemed to agree that it was within our power to do that something. But as to precisely what to do or how to do it, there were no firm answers.

As you may well recall, Lancet was the journal that published Dr. Andrew Wakefield's groundbreaking work on Childhood Autism and the link to MMR Vaccines. Wakefields sample size was 13 children - cherry picked of course - and he was being paid by some lawyers who wanted to be able to sue the vaccine companies. His work was found to be completely fraudulent. Lancet retracted the article and Dr. Wakefield now goes by Andy - his Medical License was stripped from him.

The first article talks a bit about p-hacking:

Here’s a dirty little science secret: If you measure a large number of things about a small number of people, you are almost guaranteed to get a “statistically significant” result. Our study included 18 different measurements—weight, cholesterol, sodium, blood protein levels, sleep quality, well-being, etc.—from 15 people. (One subject was dropped.) That study design is a recipe for false positives.

Think of the measurements as lottery tickets. Each one has a small chance of paying off in the form of a “significant” result that we can spin a story around and sell to the media. The more tickets you buy, the more likely you are to win. We didn’t know exactly what would pan out—the headline could have been that chocolate improves sleep or lowers blood pressure—but we knew our chances of getting at least one “statistically significant” result were pretty good.

Whenever you hear that phrase, it means that some result has a small p value. The letter p seems to have totemic power, but it’s just a way to gauge the signal-to-noise ratio in the data. The conventional cutoff for being “significant” is 0.05, which means that there is just a 5 percent chance that your result is a random fluctuation. The more lottery tickets, the better your chances of getting a false positive. So how many tickets do you need to buy?

P(winning) = 1 - (1 - p)n

With our 18 measurements, we had a 60% chance of getting some“significant” result with p < 0.05. (The measurements weren’t independent, so it could be even higher.) The game was stacked in our favor.

It’s called p-hacking—fiddling with your experimental design and data to push p under 0.05—and it’s a big problem. Most scientists are honest and do it unconsciously. They get negative results, convince themselves they goofed, and repeat the experiment until it “works”. Or they drop “outlier” data points.

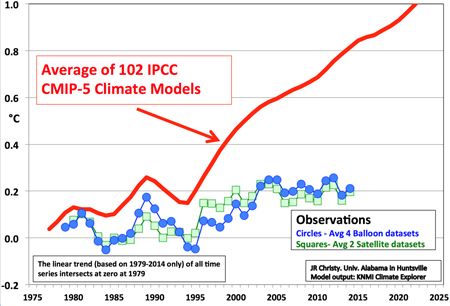

A classic example of this in Global Warming is Michael Mann's Hockey Stick where a few cherry-picked trees provided the ring measurements that was the 'knee' of the hockey stick - the place where the even temperatures soared off into the stratosphere. The tree rings accounted for the knee and all the numbers after them are actually derived from flawed computer models.

The actual boots-on-the-ground numbers simply are not there - there is no tipping point, there is no sudden acceleration of warming, the oceans are rising but will be about 0.2mm higher by the end 2100 and not the eight inches to one foot that Obama was talking about recently.